SARAH: This is At the Core of Care. A podcast where people share their stories about nurses and their creative efforts to better meet the health and health-care needs of patients, families and communities.

I’m Sarah Hexem Hubbard with the Pennsylvania Action Coalition and the Executive Director of the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium.

As part of our special vaccine confidence coverage, we’re taking stock of the latest vaccine confidence trends and some of the lessons learned so far during this public health emergency.

On this episode, Annette Gadegbeku is joining us for a community-health focused conversation regarding her work to promote vaccine confidence.

Annette is a family physician and an associate professor at Drexel University in Philadelphia. In addition, she holds various leadership positions at Drexel, including being:

Our producer Stephanie Marudas spoke with Annette.

STEPHANIE: Thanks Sarah. Annette, welcome to At the Core of Care.

ANNETTE: Thank you for having me today.

STEPHANIE: So here we are recording this conversation. It's January 31st, 2023. President Biden has made inklings that the end of the COVID-19 Emergency could happen as early as May. Where are we?

ANNETTE: Yes. That is an important announcement that will come. And things have definitely evolved and changed over the years with COVID. And it's important to still be aware of the virus, its risks, and how to continue to protect ourselves, our communities, our families, our patients and those that we serve, um, even more now than ever.

STEPHANIE: Yeah. And you, from the get-go, when the pandemic hit have been very active in various initiatives. And we'd love to hear about your experience, in rolling out some vaccination and testing initiatives at Drexel, that helped serve the community. And specifically at the Dornsife Center for Neighborhood Partnerships where you helped oversee the launch of mobile clinics.

Can you share with us some of the key community health lessons learned about rolling out these types of initiatives?

ANNETTE: So, previously, I was medical supervisor at the Dornsife Center’s Community Wellness Hub. I was there for several years prior to the pandemic. And even then, I learned about how to really assess and address the needs of the community through developing programming that was important to the community and the community's health surrounding the center, and particularly Drexel. As we study and work and learn in that community, we need to partner with the community that we are neighboring and also serving and important to learn from them as well.

So, some of the lessons learned about just implementing any community initiatives, service, programming, whatever it is that one chooses to do, it's really important to hear the voice of the community and to build trust. I think if I could whittle things down, there's so many things that are involved in this work, but if I could put at the very top is hearing voices, and building trust.

And what does that look like? It can vary, definitely. But understanding that this is a partnership, in that we are here to learn from each other, work with each other and to provide service and learn in the best capacity that we can with each other to provide the best health opportunities for our communities.

Some of the ways that we did this at the Dornsife Center Community Wellness Hub, under first Dr. Loretta Jemmott, who came and did a very comprehensive assessment of the needs. That is usually one of the first steps in any kind of community engagement. We, as particularly healthcare professionals, we like to think that we know and we like to do good things. We sometimes get ahead of ourselves in thinking we know what's best for communities and others, but it's really important to pause there and to really hear the voices and assess the needs and find out what has been done. What has not been done? What has worked? What has not worked? And how the community wants to assist you in implementing the wonderful ideas that everybody has in serving and utilizing the community. Not just going in, putting something together, implementing something, particularly going in making changes and then leaving.

And that leads to just building trust. And how you do that is just having multiple conversations with key community stakeholders. Community leaders, those who are already trusted in the community, whether they’re civic engagement leaders, whether they're pastors, block captains, whether they're already community health workers in the neighborhoods. And getting that validation that we are to be trusted and we are here to truly help and partner with the community to provide a service.

We did that also by having some weekly sessions at the Dornsife where people could walk in and ask questions. We called them Ask the Doc, and at one time we did have a nurse there. So Ask the Doc, Ask the Nurse sessions where people could walk in and ask their questions and get consultation and ask about medicines, ask about their health, ask about their numbers. And then we expanded that to some physicals, especially providing physicals for people to have employment, employment physicals, and get the tuberculosis screenings with PPDs.

We also had some community health chats. They were started out in person and then of course continued as the pandemic hit and continued. We transitioned those to virtual health chats. But these were sessions that were available. And I think we started them virtually, even before the pandemic, which was truly helpful because that was already established and people didn't have to make such an adjustment to attend these sessions.

But these were sessions where we would provide information, have some experts or consults and provide a platform for discussion for anybody who would like to join, to learn more about their health, learn more about health conditions, about wellness, various topics. And then got to see, um, again, a familiar face and a consistent face.

One of the other keys to community engagement is being consistent and showing up. And so, when people got used to seeing, I think, me and others, they knew who we were and maybe hopefully felt that we were giving great information and wanted to come back week to week to hear more.

And then, we were also a face that was in person that they could come to the Wellness Hub to see and to ask questions. So I think those were important steps and foundations that we established, particularly at the Dornsife Center, to build that community, to build relationship, to build partnership, and most importantly to build that trust.

STEPHANIE: So what we're hearing here is a multi-pronged approach that combined in-person events, virtual events, consistent events to build that trust. And to go back to one thing that you said about, early on the comprehensive assessment of needs was happening, learning what didn't work in the past and what did work. And here we were in the pandemic, pretty urgent, you know, to figure out, okay, how are we going to do this right? Curious to hear what some of those things were that hadn't worked in the past and where you could tread some new ground.

ANNETTE: Yeah, I think some of those things are just reinforced in what I mentioned. What definitely did not work and does not work is coming in, kind of feeling like, particularly as a large institution and a university, we're coming into your community, we're coming into your space, we're taking over, we're doing things and leaving or not following up.

And most importantly, too, we're collecting information, right. I'm talking about needs assessments. So we're surveying, we're asking questions, we're doing these things, but then the community doesn't hear back on what we've assessed and then what are we going to do about what we assessed. So that was really important and I think key, particularly at the Dornsife Center, in going back to the community, presenting what it is that we've learned, and how we're going to help. Proposing how we're going to address and then actually addressing it. And showing that we're here. One of our slogans is, ‘we're here because we care.’ But really not saying that in just words, but doing it in action.

So, that was one thing that was made very clear from the community voices that they did not want us coming in here. Doing things, disrupting their lives, giving hope, all those things and not being sincere. Not being consistent and then not really developing relationship and partnering and that means having continued conversations, not just getting that data and getting that information, doing something with it and moving on.

They wanted to be a part of the process. They wanted to have their voices heard. They wanted to know how they could be involved. And so, the things that we've done, we've definitely tried to incorporate the community and partner with them in anything that we do and listen and act on what they've said.

STEPHANIE: So, really creating this level of transparency, maybe transparency plus agency at the community level. And sort of segueing to the launch of mobile clinics as one of the solutions, is that something that came up as, you know, needing flexibility and sort of meeting that need to meet people where they are.

ANNETTE: Exactly. In my work, I’m a huge advocate for meeting people where they are. And as I continue to do this work, I continue to see where disparities and gaps are widened because of whether it's access, whether it's trust, whether it's misinformation, whatever it is that prevents the opportunity for people to engage with the healthcare system. And people are, are just not always coming. Even as we address those barriers, to come to our centers, to come to our offices, to come to our hospitals. There's some level of either hesitancy or inability or even a lack of desire or trust to go.

So, I believe how we can start to deliver healthcare services and support and education, counseling, all those things is to go meet people where they are. And not keep waiting for people to come to us because there's still going to be a subset of people that are not going to come. And so, yes, that was one of the basis for developing these mobile outreach, particularly for testing and vaccination through our mobile team during the pandemic. Of course, another motivation was just seeing communities, particularly those black and brown, and especially black and African-American communities in our own city, having higher rates of COVID infectivity and lower rates of vaccination when vaccines became available.

And knowing the statistics of the higher morbidity and mortality of our community, really being impacted from this virus. And I think with what I mentioned about what we had developed at the Dornsife Center, luckily we had already kind of had that foundation and so we were able to expand on that and use that foundation and the platforms that we had already established to hear the voices, to hear the concerns, to hear the questions, and to have a platform that enabled us to deliver good information, trust and information. Timely information and dispel myths and misinformation during a grave time of uncertainty and fear and anxiety and mistrust and distrust.

And so, we were given the opportunity by applying for a grant through the Department of Health in the city of Philadelphia. They were calling for people to propose programs to help with the disparities and what we were seeing and the impact of COVID. And so, I wanted to bring services where they were needed. So, we assessed our communities. We found that around our neighboring community were areas of that high infectivity, low vaccination rate when vaccines became available. So we wanted to make an impact in those areas and try to eliminate the barriers for testing and eventually vaccinations. So, we set up shop. First, we set up right outside on the lawn of the Dornsife Center in the parking lot. And we just showed up, and we showed up consistently week after week to provide testing. And we saw our numbers grow over time and definitely boom and explode during the surges that we had during the pandemic.

And so, we used that philosophy of meeting people where they are, showing up, being consistent, seeing where the need was and addressing it in the best way that we could find and know how at that time.

STEPHANIE: So in partnership with the city, you were able to launch these clinics, to address access issues as you indicated. And to actually run the clinic, what did you have to do? How did you staff it? Like what were the operational logistics that you also had to manage? I'm sure that takes a lot of coordination and what did that involve?

ANNETTE: So, luckily, we had the funding from the Department of Public Health in Philadelphia. We used that funding to, you know, hire staff, a team of testers. We had a program manager to help just coordinate the activities. But what was our pride and joy, I think, of our team was actually our volunteers. We utilized student volunteers from across the university. We had medical students. We had nursing students. We had public health students. We had undergraduate pre-med students, and other graduate students that came to help and volunteer in whatever way they could. Whether it's helping with registration or flow or giving out education materials.

We also had family medicine residents cause I'm in the Department of Family Medicine, and we made this actually a part of their community medicine curriculum to go to the sites.

And it was me and another physician, Dr. Ted Corbin, who is now moved to another university, but we particularly established the site at the Dornsife Center. Although we had other mobile sites in other areas, particularly West Philadelphia and other sites. But we were key, not just because we were doctors, but actually because we were African American doctors. And I think that held a lot of weight with the community. And thus, we also targeted our volunteers. We accepted all volunteers, but most of our volunteers were of the underrepresented communities. And, interestingly enough, we found that our participants that came through our testing and vaccinations very much mirrored the demographics of our volunteers. So, whether that's coincidence, I really actually don't think so, but I think it definitely was a contributing factor.

So, yes at first, we just had very meager operations. We set up tents, tables, chairs outside. And then, eventually as weather started to become a factor, we were able to secure a space within the Dornsife Center indoors.

And we had a place to have our testing and a place where people could wait for their results. And the biggest thing was it was free. And it was free because at that time, testing was free for everybody without insurance. And we had the supplies and we had the testing materials. We partnered with the lab, with LabCorp if we needed to send out any kind of specific P C R testing, depending on the situation of each individual.

So, I mean basic operations, and not to say that this was novel. We weren't the only ones in the city. I acknowledged that doing this. But there was not a lot. And at one point we were maybe one of very few and even only at some point during the pandemic, in our area that was providing free testing. And that was key. That was important as well.

STEPHANIE: It's interesting because throughout the past few years when we've been doing COVID-19 coverage on At the Core of Care, some issues have come up about how there were limited opportunities for residents or younger training medical professionals. So this clinic, this seemed to be able to amplify in a way where you maybe wouldn't see otherwise.

ANNETTE: We did, and that was one of our goals. We had some stated goals, of course, to meet the needs of the disparity we're seeing amongst the community for COVID. But we also heard and felt the desire of our health professional students wanting to help.

And the students’ across the city, experiences were varied depending on their institution and what they were able to do, what they were allowed to do, what they wanted to do. But Drexel is a very civically engaged institution. Our students wanted to be out there and wanted to help. And there were very limited opportunities for students to do this community engagement safely. And there were a lot of concerns about exposure for our students and liability and things like that. But yes, we were not only able to provide a service for our community members, but we were also able to provide an opportunity for students to serve, to give back, and again, learn from the community and the community members that were coming through.

And they learned to, not only how to engage, but to speak to people. They had to be up to date on their information. We were able to teach them as the guidelines and recommendations changed throughout the pandemic. You know, they were very engaged. Were asking questions and learning from us and learning about what people were coming with when they came in terms of their fears, their questions, their myths, and learned how to address those with the community members as well. So it was a great experience, I think for everyone.

STEPHANIE: And we could talk more broadly now about vaccine confidence, but to sort of make the connection here, a point that you raised about a lot of the volunteers mirroring the population coming through the clinic. And that's another theme certainly we've talked about on this podcast over the past two years about trusted messengers. And being able to relate to somebody who might be like you and having that connection. And I wonder what you and your colleagues learned in terms of vaccine confidence, through the clinics and other ways too?

ANNETTE: We definitely saw the vaccine confidence increase over time. With lots of conversation, either through our chats or conversation at our site. We had many people coming back frequently or repeatedly for testing. So we had a lot of repeat participants, whether it was because they needed a weekly test for work or they were repeatedly concerned about exposure or whatever. And so we definitely used, as vaccines became available and we partnered with Sunray Pharmacy to provide the vaccines and kind of mirror that to have a parallel, side by side, operation with our testing and our vaccinations. So as people were coming to be tested, we would educate about vaccination. Particularly, seizing the opportunity if they were negative for their COVID test and offer, would you like to get vaccinated today? We can do that for you today. And you know, that started out very small, meager. And over time, that definitely increased. And again, we saw a definite mirror, as the surges came. We saw a surge in vaccination uptake, right behind it. And that was cool to see and to learn from and to learn you don't give up on it. Again, be consistent, persistent, not pushy, not aggressive by any means.

And it wasn't about convincing people to get the vaccination. It was all a part of education and providing good information. Being a useful resource where people are getting information and using varied resources and some not, you know, evidence-based or some not very reliable. But being a consistent source of good information where we could just provide and have the conversations that people needed to have to get their own ideas and to use what information we give to make their choice.

We just wanted them to make the best-informed decision for themselves. And we did. We saw people come. Especially those that came multiple times, you know, the first time they were maybe like, absolutely not. But then we saw it change to, mm, let me think about it. And then we definitely had people that after a few times came and decided, for whatever reason, it could have been us, you know, we might be at any time planting a seed, watering a seed, helping to prune a plant in that area. Or they may have had an experience that kind of changed their mind about what to do. But the important thing is that we were there to bounce off questions, ideas, concerns, myths, and we were there to provide it when they were ready. And we definitely saw that.

So that was definitely cool to experience. And again, people sought us out, particularly those who are underrepresented that were there to ask ‘what did we think,’ ‘what did we feel,’ ‘what did we recommend?’ And again, it wasn't about convincing, but just giving informed information for them to make the best choice for themselves.

STEPHANIE: Yeah, I mean, it comes to one of your original points of the conversation about trust and you know, if there's somebody who can come and talk without judgment and just getting the facts.

ANNETTE: It was definitely good to see the shift and the change over time. And to be able to be available, to calm people's anxieties and fears and to see a transformation sometimes. And also just to have a pleasant conversation, regardless of what the outcome is. And again, just be available, for whatever is needed in that moment for people.

STEPHANIE: Yes. And you know, on that point, people who came to the clinic might end up having future healthcare experiences with you and your colleagues for their general health. Like you said, this is not a one-off, this is an ongoing relationship.

ANNETTE: And it is definitely something that we are trying to expand upon. What was really cool is one of our student volunteers from the very beginning, she created a website, and collated important informational resources for various needs. What we saw, of course, during the pandemic was a lot of the other disparities kind of just be magnified. Whether it's financial challenges, housing challenges, nutrition challenges, all these things, just magnified for our community. And so, some of our materials were geared towards helping, addressing, directing counseling for other needs. Whether they were health needs or social service needs. And so we were able to put all of that with a pamphlet and we used a QR code to direct people to those resources that they needed. And as we are continuing the operation in a slightly different way, but we're continuing our testing and vaccination at the Dornsife, we are definitely looking for ways to expand those services to address other healthcare needs, health conditions, screenings, and providing education and counseling in other areas. One of which, we got another funding opportunity to provide M-pox vaccination, along with our operation at the Dornsife. So we are actually officially starting that this week.

And then, again, we married those throughout the pandemic as well when we would do pop-up sites. We would have health screenings, blood pressure, glucose screenings, and then also our testing or vaccinations. So we did those for various pop-up events throughout the pandemic, particularly in the more seasonal months where we were able to be outside for those community health events. You're right, it's not a one and done, it's not a one-off, it's not a one condition or area type focus. We are definitely using the opportunity as we engage with the community to educate, counsel and provide other services for other things that they may need.

STEPHANIE: Keeping that in mind, Annette, as we talked about at the top of the show, you know, the end of the COVID-19 health emergency is coming. So what do things look like now, you know, how do healthcare professionals talk about COVID-19 and vaccines as part of routine healthcare? And certainly there has been a change in people's decision to get boosted further at this point.

ANNETTE: That conversation has definitely evolved over time. What that conversation looks like, sounds like is quite different and variable. Particularly now, at this current time, we've seen people's decisions get a little bit polarized by now. There's not a lot of conversation centered around so much information or trying to assess and address people's confidence or hesitancy. Because many people have made up their minds whether they're getting vaccinated or not. And I think we're at a time where I think people have heard as much as they feel that they need to make that decision. There are still a few people that can be in between. So, I think having the conversation is still important. Bringing it up is still important and I'm going to say how and why in in a minute. But just addressing where people are. I think people are a bit in a state where they kind of know what they want to do. They're pretty confident in what their beliefs and their comfort level is on the vaccine.

However, with every change, with every shift or transition, there brings more opportunity to have those discussions again. Like, this season, for example, we know that COVID increases during the fall and winter months. And so, we have other vaccines like the flu that we tend to offer and have conversations about.

And people are getting sicker during those months. And those are opportunities to have the conversation or when the new booster came out, that was an opportunity to have the conversation. But, I think shifting even away from situational conversations and making them more routine I believe is the way to go. That way that we're moving and the way that we should go. We know now that COVID is here and it's not going away. What it looks like and feels like for people may vary and change, but it's here. There's still risks involved with contracting the virus.

And, there's definitely risks for Black and brown communities. So, the conversations still need to occur, but it shouldn't be taboo, it shouldn't be situational. I think at this point it should be routine and that's what we're seeing. Some of the guidelines and the recommendations recently are coming out. It's going to be a part of the vaccine schedule. So we have all these other vaccines that we routinely provide and offer in a well visit or an office visit to providers. And so, making this now a part of your routine health conversation in an office visit. And you know, maybe we will get away from any stigma or stigmatized conversation around the vaccine.

STEPHANIE: How about access? You know, the government has covered a lot of the testing and vaccination. If this health emergency comes to an end, maybe things aren't defined yet, in terms of how, people who may not be able to afford a vaccination or testing, you know, how will they be able to access those health services?

ANNETTE: It's definitely something that we need to keep an eye on as policies change and coverage changes. We definitely saw that even while we were still providing our mobile testing, whether now the grant for the testing agencies to cover the vaccine had ended and so we had to go use people's insurance. And what about those that didn't have insurance? Luckily, there was another lab we could use to process tests. So, I think access to similar operations means mobile clinics I think are still going to be important going forward as that changes. We do have some initiatives coming through the city. I think some people are still being sent COVID home tests, and some offices and some of the health department and community health centers are able to provide testing for patients regardless of insurance. So, making sure we have that available for our patients is going to be important in our community.

I was a little sad and disappointed that the funding stopped in December. I think it's still going to be a need. I think regarding access or whatever it may be, because we're in close proximity with community members, being able to just walk up and come get tested or insurance. Granted our numbers did decrease significantly last year, which is a great thing and I think that's hopefully due to greater access or decreased need for it. Like I said, I think there's more access to home testing, home kits and things like that, so I think that contributes. But just wanting to be available again for those that need it and don't have that access. But just having it available. And I think that's why I'm happy that we're able to transition it to the Wellness Hub, who will continue those services regardless, and they'll have that available to utilize for the community. So, it's something that we need to keep an eye on and make sure that we're not leaving anyone out that needs those services.

STEPHANIE: As we take what you just said into consideration and all the various topics we touched on throughout the show, what might you want to leave listeners with in terms of any final thoughts, especially as we're here at this point, early 2023, going forward.

ANNETTE: I think it's a time we are feeling a bit relieved and less urgency about COVID and the virus. However, it's not the time to take our foot off the gas for continuing to educate and counsel and provide opportunities for people to stay safe, and particularly those populations that are marginalized and vulnerable. We need to continue to provide access, information, education and whatever services that we can provide for people and then also to continue the conversation.

I think it's a conversation that's worth having and worth bringing it to be a part of our routine healthcare and health maintenance. Our goal every year is to help all achieve their best health. That's what health equity is, and so the best, best health that they can achieve. And this is a part of it. This is a piece of it, but it's a part of assisting people to get to that health equity status where they're achieving their most, best health and wellness. So, always looking for the opportunities to not only engage, but to partner. And to provide and to learn, with our communities to achieve our best health.

STEPHANIE: Thank you, Annette, for sharing all your perspectives with us today on At the Core of Care. We really appreciate you making time to have this conversation with us.

ANNETTE: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

CREDITS

SARAH: Our special Vaccine Confidence series was funded in part by a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or CDC. The CDC is an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services also known as HHS. The contents of this resource do not necessarily represent the policy of CDC or HHS, and should not be considered an endorsement by the Federal Government.

Stay tuned for more episodes coming up in our vaccine confidence series. We’ll continue talking to healthcare professionals and frontline workers who are addressing issues that were exacerbated by the pandemic and promoting vaccine confidence.

You can find our most current and past episodes of At the Core of Care wherever you get your podcasts or at paactioncoalition.org.

And for more information about related upcoming webinars, COVID-19 resources, and upcoming trainings for nurses to obtain continuing education credits, log on to nurseledcare.org.

You can also stay up to date with us on social media by following @NurseLedCare.

At the Core of Care is produced by Stephanie Marudas of Kouvenda Media and mixed by Brad Linder.

I’m Sarah Hexem Hubbard of the Pennsylvania Action Coalition.

Thanks for joining us.

SARAH: This is At the Core of Care, a podcast where people share their stories about nurses and their creative efforts to better meet the health and health-care needs of patients, families and communities.

I’m Sarah Hexem Hubbard with the Pennsylvania Action Coalition and the Executive Director of the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium.

As we enter the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic, we’re going to spend the next four episodes taking stock of the latest vaccine confidence trends and some of the lessons learned so far during this public health emergency.

Joining us for this conversation is Melody Butler.

Melody is a member of the National Vaccine Advisory Committee as well as a member of NNCC’s Vaccine Confidence Advisory Committee. More than a decade ago, she founded and still runs Nurses Who Vaccinate. She’s also a registered nurse and infection preventionist on Long Island in New York.

Melody, welcome back to At the Core of Care.

MELODY: Thank you. I'm very happy to be here.

SARAH: So, Melody we last spoke about two years ago in 2021 when we kicked off our COVID-19 vaccine confidence coverage. Clearly, a lot has happened since then. There's now even a word we didn't have two years ago: tripledemic. From your perspective, how would you describe where we are now?

MELODY: Well, we've learned a lot since 2021, and we have a lot more tools in our toolbox to protect ourselves against all of these respiratory diseases that we're concerned about. When you talk about the tripledemic. So flu, COVID, RSV, we know how to bring the rates of infection down and we know what we need to do in order to protect the most vulnerable in our communities.

Unfortunately, not much has changed in regards to vaccination rates. Last we spoke, the vaccination rates for United States at the end of 2021, we were about 73% for people having had received at least one dose of the COVID vaccine. And here we are in 2023 and we're at a whopping 81% of people having at least one vaccine dose.

So, I'm very disappointed to see where we are right now. The fact that we have not hit at least a good 90, 95%, like we have with other vaccines, unfortunately. So that goes to show you that there is so much work that needs to be done.

We have hit a couple of walls. The public's confidence in the vaccines and in boosters have taken a hit due to variants and surges.

And the data that I really want to highlight throughout this talk, especially when we talk about the COVID vaccine, is how, while it may not protect you from getting sick, you may still catch COVID, despite being vaccinated but it's going to do an amazing job keeping you out of the hospital. It's going to keep you from developing severe illness, complications that could follow had you not been vaccinated.

SARAH: Hard to pinpoint exactly. But it seems like people are sicker than before with the flu going around, COVID, the common cold. Do you agree with that?

MELODY: I do. In fact, we're in a very rough flu season. To date, today is January 24th. For this flu season, we've had a total of 85 pediatric deaths. That's awful. Last year, for the flu season of 2021 to 2022, there were 45. We haven't even hit February yet, which is normally our peak for flu season, and we have more than doubled the pediatric death rate from last year. I really do fear because usually, what we saw before when we had a bunch of Flu A. And what tends to follow Flu A is Flu B and that's going to be rearing its very ugly head very soon.

Now the thing with flu is there's no in between for flu. Either you have the flu or you don't. There's no, Hmm, I might have the flu. If you have the flu, you're knocked out, you're sick at home. However, you're contagious for about two days before you can show symptoms sometimes. So think of all the people you come in contact with in two days.

And I do worry though, because now thankfully the flu cases are coming down, but Flu B is known to piggyback on top of Flu A. So, a really important message that, uh, we need to get out there to the public is that even if you have had flu earlier this flu season, you are, um, even more at risk for complications should you catch an additional flu strain later in this season.

SARAH: And what have you been hearing and seeing in response to the new COVID-19 bivalent booster? How's it being received? What are the risk calculation conversations sounding like?

MELODY: The rollout of the COVID booster, the bivalent booster, has been very tricky and there's still lots of confusion surrounding it. And unfortunately, a lot of people still don't know that they are a candidate for it when they very much are. There's really four reasons. One is they don't realize that they should be getting it. Maybe they got a vaccinated earlier this year with one of the earlier boosters, and they don't realize that they're a candidate for this current one. Number two is they're too busy. Unfortunately, access of the booster is not as easy as it had been earlier in the pandemic. Some locations only have the booster being given out certain times and certain days of the week. I know that even doctor's offices don't always carry the booster. You go to the doctor's office for a physical and then they say go to the pharmacy to go get your booster. And people aren't making that second trip; which then leads us to number three. People are forgetting that they need the booster. Then, number four, people are worrying about side effects.

SARAH: And also side effects that can make it difficult to work. I mean, combining that, with being busy. If you know that you're someone who's going to be sick for a day or two after you get your booster, sometimes that's extra hard to schedule in.

MELODY: Of course. And we know we don't have that leeway that we once had with the original COVID vaccines, where there was even days allotted by some businesses that if you got the COVID vaccine, if you developed a fever the next day, you were not penalized. And it was okay. It was recommended that you actually stay home and recover from getting the vaccine because they realized how important it was to get vaccinated. And it kind of seems that we've gotten away from that. It's an all hands on deck and we learned in the early days of the pandemic how to work all hands on deck.

SARAH: I think you touched on several things that were really important there, but kind of what stood out to me was that frustration. And, and it touches on a little bit of what we talked about in some of the past seasons too, about the burnout, the burn down, the fatigue. Like how could this have gone? And what do you say to your colleagues who are struggling, who are frustrated, you know, who are feeling alone?

MELODY: We all need pep talks. No matter where you are, no matter how you're working in this field, whether you're doing frontline nursing care, quality work, data reporting, public health, public education. Seeing the statistics, knowing your loved ones are getting sick, seeing family members refuse to get vaccinated then develop complications. All around, it can be frustrating and we always need to help support each other. So when we keep that in mind, we need to really make sure that we're building upon all the resources that we need to have laying out there for us, because we never know when we're going to need to step back and then tag in our partner to kind of go in there for us to kind of take over the education or take over the patient care. It’s something we need to make sure that we do a better job, relying on one another and using all the different skills that we have. I really want to say going forward, for the next winter, like let's say we know that this is going to happen again, we need to have more resources for nurses to have downtime, for doctors to have more flexibility of sick time, right?

We had even healthcare workers getting very sick during this last surge, and they were doing everything they can to protect themselves. Unfortunately, sometimes you're still exposed at home or in the community and making sure people know that they don't and shouldn't go to work sick. Making sure that we're really reinforcing and encouraging and highly encouraging self-care. So if we take away anything from this most recent winter, it's the continued need of taking care of each other, taking care of ourselves, because we're in this for the long run.

This is our new normal. And as much as I hate that expression this is it. This is what we have to really kind of focus on and come up with a good game plan in dealing with.

SARAH: And clearly, you've talked about the impact of illness on kids that we're seeing. So, looking at vaccination, I think specifically COVID-19 vaccination, how's that looking for kids? Especially under the age of five.

MELODY: So as of January 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics continues to recommend the COVID-19 vaccine for all children and adolescents six months of age and older. As long as they don't have any other contraindication to vaccines. With that being said, right now, we have about 1.9 million children, six months to four years, who have received at least one dose. 1.9 sounds like a lot. Unfortunately, that represents only 11% of that age population.

So that means there are 15.2 million children between six months and four years to receive their first COVID-19 vaccine. And what's interesting is that vaccination rates really do vary from state to state. You have some states that are at 2% and you have some states that are at 40%. So there is a lot of work to be done. And when we talk about COVID-19 vaccine for the children under five, it's really important to stress to the parents when we're educating them, making the recommendations, is how safe the vaccine is, how we continue to monitor the vaccine for any type of adverse reactions or safety issues and whatnot.

SARAH: So thinking again about kind of where we are now and where we've been, access has been a barrier throughout the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. So, to what extent is vaccine access still an issue? Really, access to both vaccines and testing? And how do you see that changing as the public health emergency declarations are starting to expire?

MELODY: So, I've come to learn that, you know, I live in New York where everything's pretty much centralized. We have pretty good access here, and it's very easy to forget how rural some parts of the country can be. Well, a lot of the parts of the country are. And in talking to colleagues around the country, I know that it can be very difficult right now as we stand to get boosters, to make appointments, to have that availability to drive an hour or so to a vaccination site to get vaccinated. So, when we talk about the emergency declaration ending, I'm really concerned. There's going to be major changes that are going to occur. The COVID-19 federal emergency declaration provided free testing. It provided free vaccines and even free treatments such as some of the antibody treatments that people were receiving. What's important to know is not all of these items will go away, but a lot of them will no longer be free. So people, if you don't have insurance, they'll no longer be a pathway through Medicaid for free COVID testing, vaccines or treatments. And then for Medicare beneficiaries, there is going to be a cost sharing requirement. Hospitals are going to be affected by this. Hospitals will no longer receive the 20% payment increase for discharges of patients diagnosed with. when this expires. And we know that when you have a COVID-19 patient, it's complicated. So, to lose that funding that can help provide for additional nursing care, that's very troublesome. It's something we should be worried about. And, you know, I mean that's just a small snippet of the concerns that I have when this does expire.

SARAH: So, as we're forecasting out, you know, what are the things to be paying attention to, what might we expect to see in terms of vaccine confidence trends? You know, the next six months, the next year, what do you see coming?

MELODY: I foresee us in the healthcare community having to continue this uphill battle. We are continuing to push against misinformation. We have to push against this adversity to mandates. And also we have to push against hopelessness that we see in our patients. People are very disappointed that the COVID vaccine does not prevent illness. We have to stress how amazing it is that the vaccine keeps you out of the hospital just like the flu shot. The vaccine prevents severe complications and it prevents death. It does a great job at keeping you alive, and that's such an important point that we need to stress to the public, to our patients, to our communities. But we need to do a better job at that. And we need to continue to push back even harder against misinformation. The misinformation and the anti-vaccine movement organizations, they're only getting stronger. Social media has its ebbs and flows in regards to how it regulates and how it decides what's acceptable and what's not acceptable. And unfortunately, right now we are dealing with really, really serious conspiracy theories. And it's very damaging to the public's confidence. So, we need to have a more collaborative effort in pushing back against these very negative narratives and sharing stories of how safe it is and how important it's to be vaccinated. And how being vaccinated is one of many of the tools we have to protect ourselves. Hands, hygiene, washing your hands, wearing a mask. Being aware of your surroundings in a crowded area. I, myself, when I go to shows and if I'm like, you know, attending a, a musical or a play, or even a concert, like my kids' concerts, sometimes those auditoriums can be very packed and you’re right on top of each other. I put a mask on because I know I'm going to be in this one spot for a good two and a half hours.

I hear the person behind me coughing and sneezing, you know what? I don't want it. I don't care what they have. It could even be a mild cold. I don't have time to get sick. I'm going to utilize all these tips and tricks that I have, you know, using Purell. I'll carry Purell with me and wash my hands.

So, we need to continue to really educate the public. We need to really work together and to continue to encourage one another to be vocal advocates whenever we can.

And if you yourself don't know the answers, at least know where to direct people to go. At NNCC, there are many resources that people can utilize in regards to updating themself, webinars, and other educational pieces they can use to stay up to date.

The CDC has a great reference. They're called the COCA Calls where they put out on a monthly basis keeping everyone up to date on the effectiveness of vaccines. And the latest outbreaks and important information the healthcare providers need to know. Vaccinate Your Family is another great resource that we direct people to go to. They have a lot of information that's easy for the common lay person to read. You don't have to be in the medical field to understand the information they put out there. And if you're looking for like-minded people who are vaccine advocates, who appreciate the science, maybe don't have a huge scientific background, but you want to do your part. There's an organization called Voices for Vaccines that I'm also a part of that we work really hard to just encourage the regular person to be a science advocate.

SARAH: Can you tell us a little bit about Nurses Who Vaccinate? What's going on with that right now?

MELODY: Thank you for asking about Nurses Who Vaccinate. We are sharing some very important information on our social media pages, making sure that our members and our followers are staying up-to-date on what they need to know about COVID and flu, RSV, Monkeypox. We continue to be a reference point for nurses and healthcare workers to collaborate to come up with ideas and a game plan in regards to education and advocacy, whether it's in their own workplaces, in the community, in the nursing field. We're working with organizations to host some events that are up and coming, so stay tuned with that. We're looking forward to hosting HPV vaccine awareness events. We're going to be looking to partner with one of our partners Shot at Life for an upcoming summit, where that’s going to be involving our members going out in the real world, doing face-to-face advocacy with some of our legislators and educating, them on what they need to know about vaccines and making sure they're up to speed on the up updates and evidence-based information. And we'll be working with our members to continue to provide that support that's very much needed, especially those who are vocal vaccine advocates. Sometimes it could be a very lonely world out there for those who are passionate about vaccines. And it's important that they know that they're not alone. And we are here as a resource, as a safe place for them to come up with great ideas that continue that momentum and get the information out there to the public and to renew their sense of service.

SARAH: So, before we come to an end, any final thoughts you want leave with our listeners?

MELODY: What I would like everyone to walk away with are three points. One, it is not too late to get vaccinated and it's not too late to convince your loved ones and family members to get vaccinated. Persistence is key and continue to be their source of information to be that place they can go to ask questions in a safe venue. Two, don't give up. Sometimes it can be very frustrating. That was our common theme of the night. But don't let the frustration keep you from doing good work. Continue to fight the good fight. We need to protect ourselves, our colleagues, our patients, and our community from these preventable diseases. And that's what they are. Number three, they're preventable and that we can only prevent them if we use all the tools in our toolbox. So, remember, it's not just about vaccines. It's about wearing a mask. It's about staying home when you're sick. It's about washing your hands. The simplest of simple things. I want to make sure that people understand all these things do add up and they can play a huge part. Making sure good ventilation systems. Oh, we could talk an hour about that. Even more than that, right? I wish we had the time. But working together to put all the pieces of the puzzle together, and hopefully maybe next winter, we won't see the crazy surges that we saw, and we won't have 80 kids dying from the flu.

SARAH: Thank you so much for everything that you're doing to keep this movement strong and the contributions that you're making personally and and professionally. And of course, thank you for making time to join us on At the Core of Care.

MELODY: My pleasure. I hope to see everyone out there. Stay safe and stay healthy.

CREDITS

SARAH: Our special Vaccine Confidence series was funded in part by a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or CDC.

The CDC is an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services also known as HHS. The contents of this resource do not necessarily represent the policy of CDC or HHS, and should not be considered an endorsement by the Federal Government.

You can find our most current and past episodes of At the Core of Care, wherever you get your podcasts or at paactioncoalition.org.

And for more information about related upcoming webinars, COVID-19 resources and upcoming trainings for nurses to obtain continuing education credits, log on to nurseledcare.org.

At the Core of Care is produced by Stephanie Marudas of Kouvenda Media and mixed by Brad Linder.

I’m Sarah Hexem Hubbard of the Pennsylvania Action Coalition.

Thanks for joining us.

.png)

To celebrate Black History Month, we are honoring Black healthcare leaders who have contributed to the advancement of our health and healthcare systems. Their contributions continue to have a long-standing impact on us all. To celebrate their legacy, we will be spotlighting Black nurses, advocates, and other trailblazers and their achievements.

Learn more about the Historical Black Healthcare Leaders we are highlighting this month.

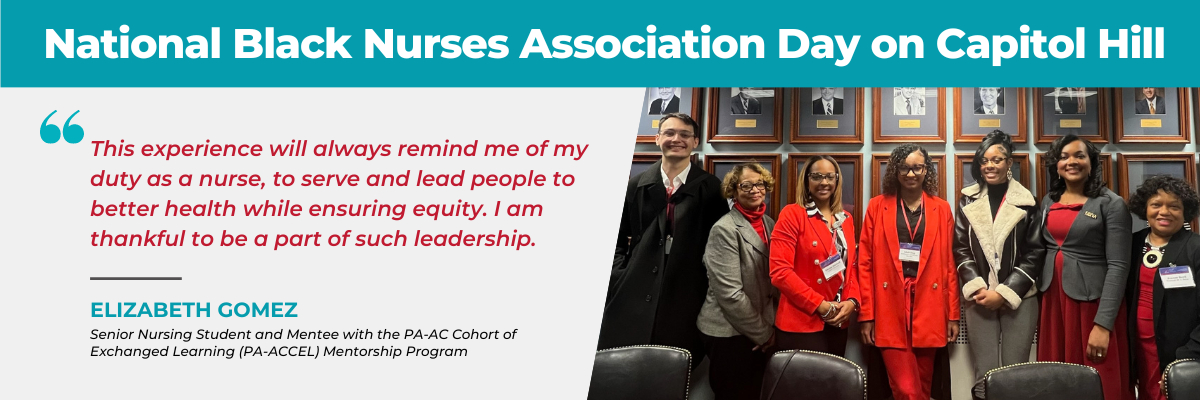

As we honor past nursing leaders, we also celebrate the future of nursing. On February 2, 2023, the Pennsylvania Action Coalition had the pleasure of attending the 35th Annual National Black Nurses (NBNA) Day on Capitol Hill. This forum is dedicated to congressional health issues and policy. Student mentees from the PA-ACCEL Mentorship Program, a partnership with Lincoln University, learned about seven key legislative priorities advancing health equity. These legislative topics included:

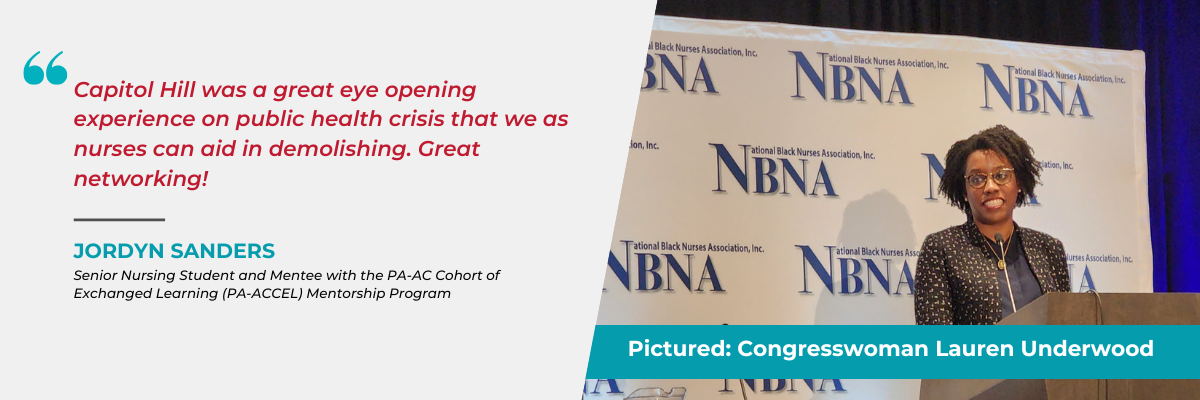

Mentees in the PA-ACCEL Mentorship Program share highlights about their experience at NBNA Day.

Pictured below is Congresswoman Lauren Underwood who currently serves as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives. Underwood represents the 14th Congressional District of Illinois, officially taking office on January 3, 2019. Congresswoman Underwood is a trailblazer, being the first female, the first person of color, and the first millennial to represent her community in Congress. Learn more about her accomplishments and work.

The Geisinger School of Nursing, in collaboration with the Pennsylvania Nursing Workforce Center (PA-NWC) and the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium (NNCC), is addressing nursing faculty and instructor shortages by participating as one of ten Nurse Education, Practice, Quality, and Retention Clinical Faculty and Preceptor Academies (NEPQR-CFPAs).

The collaborative is executing the program with funds awarded by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), CFDA#93.359 and is focusing on HRSA Region 3 (including Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C.).

The purpose of the NEPQR-CFPA is to close the clinical faculty gap by leveraging new and/or existing nurse education and forward-facing staff nurses to participate as skilled clinical instructors and/or preceptors through the development of a comprehensive, self-guided training program.

The CFPA 101 facilitates the growth and development of bedside nursing staff, nursing schools’ educators, clinical faculty, and preceptors, which in turn will improve the severe nursing shortage through stronger clinical educational opportunities that has worsened since the pandemic. The CFPA 101 aims to empower and encourage nurses to work as preceptors and clinical faculty to undergraduate PN and RN nursing students during clinical rotations and will be widely available for use by healthcare systems and academic institutions in October 2024. The CFPA 101 was created by Geisinger, PA-NWC, and NNCC.

To develop this curriculum, the PA-NWC assembled an Advisory Board reflective of diverse practice areas, academic pathways, geographic locations, and populations served across HRSA Region 3. The Advisory Board oversaw curriculum development and determined metrics of review. The PA-NWC and Advisory Board stakeholders ensured that the course content is engaging, thoughtfully articulated, and caters to a wide audience. Currently, employees across the Geisinger health system are piloting and evaluating the curriculum. The PA-NWC and CFPA Advisory Committees will use lessons learned to prepare the program for implementation across the HRSA Region 3 beginning in the Fall of 2024.

Meet the CFPA Members

We are pleased to announce that CFPA 101 is now available to healthcare systems and individual nurses in HRSA Region 3.

Eligible CFPA 101 participants include undergraduate nursing student preceptors or clinical faculty with at least an LPN or RN license in good standing. The CFPA 101 training addresses professional development needs of clinical faculty and preceptors working in a variety of settings. However, this initial version of the CFPA 101 curriculum includes teaching scenarios and activities particular to the ambulatory, in-patient setting.

The CFPA 101 course curriculum is divided into 6 modules. Some content is specific to a particular module, while other content areas carry across modules. The modules are as follows:

Each module contains clear learning objectives, interactive learning activities, periodic learner knowledge checks, and links to vetted resources. Enrolled CFPA 101 learners must complete each module in order, pass knowledge checks, and submit a series response capstone to be reviewed by Geisinger's expert reviewers. The CFPA 101 course is hosted on Geisinger's online learning management system and open to enrolled users from approved pilot testing organizations.

Nurses who enroll in and complete the CFPA modules will be awarded a certificate of completion and can receive continuing education units (CEUs) that can be used to fulfill educational requirements for re-licensure and/or nursing certifications, for a small fee. In addition to the CEUs, nurses who participate in the CFPA 101 course may be eligible for a financial incentive based on level of participation. Grant funding for financial incentive payments is not guaranteed and will be determined on a case-by-case basis with identified pilot sites.

To access CFPA 101, please go to Geisinger’s website.

If you have CFPA specific questions or need assistance accessing CFPA 101, please email .

The Clinical Faculty and Preceptor Advisory Board is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $4 million dollars with no percentage financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

For more information about the CFPA 101, download the flyer here.

SARAH: This is At the Core of Care, a podcast where people share their stories about nurses and their creative efforts to better meet the health and healthcare needs of patients, families and communities.

I'm Sarah Hexem Hubbard with the Pennsylvania Action Coalition and the Executive Director of the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium.

As part of our special training coverage, this episode features a conversation about Centering Trauma Literacy in the Health Center Medical Home. We’ll hear how providers and health systems can cultivate trauma-aware practices as part of their delivery of care.

My colleague Jillian Bird, Director of Training and Technical Assistance at the National Nurse-Led Care Consortium, will lead the conversation. Through a wide variety of ongoing programming, Jillian and her team help support providers working at community health centers across the country.

MUSIC UP

JILLIAN: Thanks Sarah.

Our guests for this conversation are Kathleen Metzker and Sara Reid, and they’re joining us by Zoom.

Kathleen works in Philadelphia as the Director of Integrative Health and Mind Body Services at the Stephen and Sandra Sheller 11th Street Family Health Services of Drexel University. In this multidisciplinary health care setting, more than 6,000 patients access a range of services, including: primary care, behavioral health, dental services, and health and wellness programs.

And Sara is based in Boston where she is a health educator, support group facilitator and consumer board member for the Boston Healthcare For the Homeless. Sara is a public speaker and delivers trainings on transgender priorities, including teaching medical and behavioral health providers how to provide gender-affirming healthcare.

Welcome Kathleen and Sara to At the Core of Care.

KATHLEEN: Thanks for having us here Jillian.

SARAH: Thank you.

JILLIAN: At the beginning of each episode, we always like to ask our guests why they do the work they do. Kathleen, can you start us off?

KATHLEEN: Well that's a very good question, why I do the work that I do? I think it's natural for me to want to do work that is in the service of others. There are so many people that show up for their job to get a job done, to get home, to have the rest of their lives. But remembering that we are in constant relationship with one another is a core principle in my own life. So I’ve really had the opportunity for that to show up in my personal life every day. And it reminds me that I'm alive. And that is why I do the work that I do.

JILLIAN: And Sara, what about you?

SARAH: Actually a couple of reasons. As a mother of two, grandmother of four, you know, thinking about making the world a better place and, be better than I found it is kind of like core to who I am. And also, I've spent the last 30 years in one form of counseling or another, and you know, around the issue of trauma, the medical system itself has been very traumatic, because of kind of the era that I came out in. I'm a trans woman myself, and it was just all barriers, all stigma. We were almost universally discriminated against. And, you know, I would like to be the young 18-year-old starting out with a good prognosis a good outcome for the medical interventions and, and look forward to a whole life of you know, just being myself. But it wasn't possible for me. And I guess, one of the ways I make use or reconcile the lost time of, you know, big chunk of my life is to make sure that it never happens to anyone else again.

I struggled to get to where I am. I went through six years of reparative therapy, or they call it conversion therapy, to try and kill it off. And then having come to the end of that, I went in looking for gender affirming care, and I just couldn't find it anywhere, you know, I ended up getting referred around like a hot potato. And then interacting with the community that I directly work with, I found that, you know, my story is kind of pretty average. And the stories that have been told to me, you know, I kind of wanted to do something about it. But at the time, you know, I was having the conversations I didn't have any direct way to make the medical interaction with my community better, but I've kept it in my heart and opportunities have risen, I've taken an opportunity to kind of speak to those issues and keep the people that were kind enough to share their stories with me in mind as I went forward to do some teaching, and help people understand better.

JILLIAN: Thank you very much for sharing those perspectives with us and before we dive into our discussion, let's first hear about the communities you're currently serving and what key needs you've been concentrating on addressing?

SARAH: So my entry point into working mainly with my nurses, you know, I love working with my nurses, they've been, you know, a godsend to me, and they're just some of the finest people I know. But the sort of my entry position was seeking out help. And the most welcoming, friendly place to trans care was Boston Healthcare for the Homeless, believe it or not. Absolutely no discrimination or stigma, they've been wonderful. And with that, my interaction with patients has gone two ways. One is I'm interacting with our general patient population, as well as I sit on the board of directors. So I'm, I'm like on both levels, I'm with the executives monthly and then interacting with patients and peers. And then my, you know, where my heart lives is where healthcare touches the needs of gender affirming care for trans identified people. And I've had quite a lot of experience with that over the last decade. Things are changing in some ways, but we've still got a long ways to go.

JILLIAN: And Kathleen, what are the needs you feel like are being addressed in the communities that you're serving currently?

KATHLEEN: Thinking about it through the lens of the health home, we're a federally qualified health care center. So we're operating under the assumption and the knowledge that the greater majority of our patients live below the poverty line, low-income, socio economic status. Our demographics of approximately 6000 patients, where about 75% individuals identify as Black and African American, and the rest of the breakdown, pretty much divides between white, Latino and other. But the thing we know about individuals and communities like ours, that are really up against more social determinants of health. And there's an increase in adverse childhood events, which, as we know, then impacts health outcomes of mind and body later on in life. So thinking about this through a trauma-informed care lens, operating under universal precaution. And keeping that in mind as we're interacting with our community and patients. Also the Health Center is set right in the middle of four public housing communities. We've been there over 20 years. So especially as we emerge from the pandemic, I keep reminding my team or reminding each other we almost need to act as if we just got here, right, because we're a university affiliated medical home. So there's the history of mistrust, needing to build trust and relationships. And even in the 12 years that I've been there, generations have changed. So what used to be the children of clients are now the parents of the children, and caretakers of their elders. There's, of course, the impact of the pandemic, and the increase in community violence in Philadelphia. So all of these things are impacting the well-being of the individuals in the communities that we’re intended to serve. So really keeping all of these things in mind and understanding the complexity of those needs, is really where we're landing right now.

JILLIAN: Thank you. And I always think of where you are and the organization that you're working with as being a leader in this space, for so many reasons. And hopefully, we'll be able to touch on some of those in this discussion. But kind of following in that leadership, we've seen of continual shift and healthcare spaces to try to be more trauma informed and trauma literate, and have a more holistic understanding of what being trauma aware is. So I'm curious, Kathleen, as you think about your own organization, and also this general evolution, are there some real examples at your health center where you work that you might be able to share that sort of really highlight or encapsulate these concepts and then how they look in practice?

KATHLEEN: Yes, and I appreciate the use of the word holistic. And at the same time, I think that feels from a healthcare or scientific lens, sometimes it feels a little soft. So if we could even recontextualize it in thinking of trauma informed care as a systems approach rather than addressing technical needs.

We're also talking about humans interacting with humans, which becomes complex, and cultural perspectives. And when we think of the patient provider relationship, even through a trauma informed care lens, the ideal would be recognizing that potentially trauma has impacted this individual, their behavior, their health outcomes.

Then we have the provider patient relationship that has inherent power dynamics. So when we're considering communities that would otherwise be considered marginalized or disenfranchised. These kinds of buzzwords of people being treated like others, those power dynamics play a big part. So understanding that and that felt and lived experience for the patient and the provider, and the provider who's also having a very human experience and potentially carrying their own trauma. And even just their own day to day lives. So I always refer to trauma informed care as this practice of being skillful humans together. So thinking about how we use language is significant.

So really, we're cultivating a type of culture in professions who aren't necessarily trained to understand trauma, or to understand the lived experience of those that are oppressed. So we need to do that in ways that are relatable.

So really a real time example of something that we're navigating in this moment is how we're responding to patients that we would consider or might be called disruptive or having outbursts. So even just that language like this is an outburst? And how do we manage de-escalation can feel oppressive to that person and feel marginalizing or dismissive. So what if we change that language a little bit? But then how do you how do you train the provider to think about that?

So on another hand, if a patient came in with a limb, that might be symptomology of an injury in the leg? So looking at an analogy here, if a patient comes in with behavior that feels outside of cultural norms, so an outburst for example, that's a symptom, perhaps of trauma, or that something has happened to this person, not that something is wrong with this person.

The neurobiology of trauma, so what does that really look like? And how does that show up and, at the same time, needing to equipped ourselves then with those soft skills of compassion, active listening, of self care, and all of this needs awareness.

So for example, a provider, taking that pause to ask themselves, how am I doing in this moment? How am I really feeling in my mind and my body and my heart? And in the midst of the culture of health care, how can we possibly take care of our nervous system? It's fast, there are expectations around time. There's a lot of complexity. You're up against a lot, especially now when one of the things that we're up against his staff turnover and being short staffed as a result of the pandemic.

So all that being said, at our health center, staff wellness is emphasized on a regular basis. It can't be just something we say on paper needs to be ongoing. And one of the skills that we use is the practice of mindfulness. And mindfulness supports these qualities of compassion, active listening, self-awareness and self-regulation. You can't regulate yourself, if you haven't checked in to begin with to know that you need it. So becoming more self-aware in our relationships with one another, again, this idea of being skillful together. Some of the ways they we do this more practically, is we at the beginning of our meetings, including our huddles, we have check ins “How are you feeling in this moment? Do you need any support today? And who can you ask for that support?” And these are some of the questions that come out of the sanctuary trauma informed care model. So I want to make sure to give them credit.

We have moments of mindfulness at the beginning of most of our meetings. It could be real practical mindfulness, maybe we're doing some breath awareness, maybe some body sensations and grounding. We have created physical spaces for respite rooms, so that if staff need to step away, because often in healthcare setting, you don't have privacy during the context of your workday.

We have daily practices at lunchtime, whether it's a yoga practice, meditation practice, maybe engaging in some art or music therapy. We are fortunate to have a fitness center on site. And I realize that not everybody has these things. But there are ways that you can create these things. All you need is a room. You could put on a YouTube video, and you could do yoga together for five minutes, or you could do a five-minute meditation. So there are always ways to make these things work.

And another thing we find very helpful is visual cues around the building. We have gold stars all around the building. And they're reminders for you to pause and to check in with yourselves. We asked staff to submit quotes of affirmation or encouragement. And then we have handwritten signs all around the building that staff were asked to hang in places that felt relevant to them are felt visible to them. So as they move through the space, and as the patients move through the space, they see these.

And last example offer is we created something we call the mind body toolkit. So it's both a visual cue that hangs, it looks a little different right now because of pandemic. It's more technologically oriented, but their visual cues and primary care tools that both the patients and the providers can use to help themselves to pause. Maybe it's little signs of affirmation, or breathing practices, or even a stone just to hold for sensation and grounding. Another benefit of that in addition to helping someone just kind of get settled, get present. It improves the relationship between the provider and the patient so that they can they can be humans together while still attending to the to the needs of the visit.

JILLIAN: Thank you so much. Yeah, I'm thinking about how you're giving very concrete examples of how both the care team, the members of the care team, and those that are in the health care delivery setting are also working on themselves, and at the same time able to support the patients that are coming in. I'm imagining that creates an environment where patients feel this sense of comfort that they know that there's work being done on both sides here. It's not just as one direction of I'm being told that these are things I need to work on, but that in fact, the entire environment is committed to being trauma informed, and also supporting the health care team. So I'm curious, Sara, from your perspective, and from your lived experience, as well as the expertise you have with training health care providers, what considerations around trauma are you highlighting for providers and the health system to keep in mind as part of their delivery of care?

SARAH: Where I usually try to meet them, the providers is with what they're experiencing. And I do that with whatever community I'm working with. So when I am doing a training, I'll always say, as you know, is as to my community, you'll find that we're not always the easiest patients to have or to deal with. We sometimes have short fuses. Sometimes we seem angrier than other patients. Sometimes, we’ve got a, what they call a hair trigger for switching a friendly hello into something escalated. And I think understanding a little more about what happened to this person on the way to this visit.

I worked customer service for a lot of years in retail, and I learned that no interaction, even with an angry customer, it's never about me. So, with our patients, they have had, ongoing trauma throughout their, say the last month. They may have had 50 things happen to them. Some of the things may have happened on their way into the meeting. Sometimes people feel empowered by picking on people they feel are fair targets that they can get away with. People get misgendered, rejected by their families. Some have lost jobs.

I’m at the intersectionality between undocumented asylum seekers, Latino community, and then we have a lot of substance use. This is just in our general practice. So I think to some of what Kathleen was saying is, you know, we got to have a team attitude towards this, you know. What I love about my clinic Health Care for the Homeless is that it is always a collaborative effort from CEO all the way up to the patient, you know. And we are a team, and are always checking in with each other. And it's a genuine thing, which is, I think, in some ways, you know, rare and wonderful.

But back to the patients, you know, they'll come in and they'll be upset, maybe you use the wrong pronoun or something. And the easiest way to deal with this to say I'm sorry and move on. But in understanding or having some sort of a picture of what they may have going on in their lives.

If you take a step back, take a breath, and realize, you know, it's not about you. And then don't patronize because that's another one of our triggers. We know when we're being patronized, and somebody's being insincere. But I think just, by seeing another human being somebody's kid, somebody, sibling, maybe somebody's spouse, or parent.

You know, that this is a person just like me, that goes a long ways. Kathleen mentioned about patients, feeling like they're listened to. One of the greatest things, twice, I've had it happen in both points in my life, were turning points where I met a new group. Well, the second time I met a group of trans women from Cambridge. They were all Latinas. And I remember going down the list of the mess that I was in at the time. I was going through a divorce, I wasn't going to see a paycheck for the next 15 years because of my own sense of shame. I had taken on all the marital debt. I was still trying to be as involved with my children as I could, working couple jobs, with no money to no place to live. And on and on and on. I remember talking to this just wonderful, beautiful, trans woman from the community. And she listened to me and she says, ‘Oh, that sounds about that sounds about right. That sounds about like most of us what we're going through. I believe you.’ And just those three words, I believe you. It just means so much.

And I found it, you know, going across to other groups that we work with that that really helps a lot. If you have a patient, maybe who's coming from a vastly different culture and or somebody that's dealing with a mental illness, and they're having things that we would consider not necessarily real, but we can still believe that it's real to them, and kind of get in get in to tell me more about that. That sounds really scary. And you can be real about it to do other people see this person talking to you or is you know, just like is it just between you and them. You can contextualize it and kind of get into it and just be supportive of them. And that's a good place to start. Once they feel listened to you can start building up from them.

So back to us being rough patients. I always say you know, you may be the first person in a month to give us a break. So maybe you don't understand this patient in front of you, you don't understand why this is, this is such a challenge or obstacle for them why this is such a struggle. But just that human contact, that genuine sense of I believe you. Let's start here, let's start working on these things right now and see where you are in a few years.

JILLIAN: I hear a lot and what you're both saying the power of listening, and seeing people, being with people. And in so many ways, it's speaking to really supporting that psychological safety that I don't think is often considered and sort of the flow chart, you know, how the patient flows in and out of the clinic, and, you know, all of the logistics and operationalizing that we do to ensure that our medical system is functioning. We want to put the human back into the center. And really considering that psychological safety is as important, I think, in many ways as to, you know, finding the right diagnosis and continuing to build on the right care plan and making sure the medication is correct. And are you seeing psychological safety? Or something along those lines being part of how you consider care that's being received? Or if this is quality care? Is that part of the conversation for either of you?

SARAH: Yes, actually, it's been astonishing. My nurse and I, that I partner with, in a lot of the trainings, we were invited to be part of the transgender Task Force at Boston Medical Center, when they outwardly declared themselves as having a comprehensive trans care component of their practice. Now, that's not something anybody would have advertised 15 years ago. But strangely, Healthcare for the Homeless did 13 years ago, and I keep telling my nurses how unusual and wonderful that is that they actually said, Oh, no, this is what we want. It's it wasn't like the last thing on the list. It says, No, we're a transgender clinic. And everyone's like, wow, that's different. Because there's so much stigma back then.